A Structural Approach as Ethical Response to Morally Void Testimony

Koch in a recent essay provides empirical grounding from 203 documentaries to establish that no universal ethical code governs perpetrator representation. This framework of a so-called “situated ethics” instead of universal standards directly applies to Luuk Bouwman’s approach. The film uses Teunissen’s own audio interviews, and we soon realize that his language is eloquent and persuasive, but his narrative is structured around the complete absence of moral understanding, so every rationalization and every reframing of his actions further falsifies the past. Therefore, including historians Rolf Schuursma and Egbert Barten, and showing their reactions was essential to counterbalance the extensive “screen time” given to Teunissen, and to provide facts and evidence, while establishing authority.

The distance of many years allows Schuursma to reflect on the recordings with fresh perspective, occasionally finding himself startled by what was said, so the meanings of those original statements undergo a process of revaluation through a retrospective lens. Through this Bouwman demonstrates a fundamental lesson, that testimony’s value lies in what it lacks, that witnessing depends on impossibility and that ethics must begin from gaps rather than fullness. This critical recontextualization of the perpetrator’s shameless self-justification renders The Propagandist both a documentary about propaganda and demonstration of documentary’s power to counter propaganda.

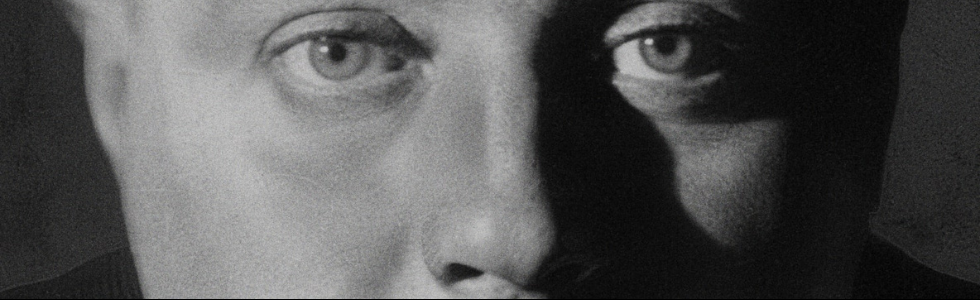

Teunissen describes overseeing propaganda, turning people into authorities and using his position to persecute critics, yet he presents this as a story of professional ambition and bureaucratic necessity, his testimony contains no aporia because he experienced no trauma. The documentary poses the question that how do we respond to testimony that is morally void? Bouwman’s answer is structural rather than explicit, the film itself becomes an ethical act, it builds a structure that postpones judgement while methodically building the case against the propagandist’s own propaganda about himself.

The thoughtlessness that marks the failure to think from another’s perspective explains Teunissen’s “smarmy candor”, clichéd self-justifications and self-aggrandizement in the 1964-65 audio interviews. Teunissen represents not a monstrous evil driven by Nazi ideology, but an opportunistic collaborator who couldn’t think beyond personal advancement to consider consequences. Understanding perpetrators doesn’t mean condoning – it serves prevention by revealing how ordinary people enable extraordinary evil. Teunissen is an exemplar of Arendt’s banality of evil concept, as he demonstrates banality through his openness, lack of remorse and casual tone of retelling his crimes. It's also interesting how the documentary inverts Agamben’s theory of testimony about the “complete witness”, who remains forever silent defined by an experience so extreme it exceeds language. The Propagandist shows that the perpetrator cannot stop speaking, he speaks for 7 hours and 45 minutes in archival audio, yet despite this verbal abundance, there is a profound sense in which Teunissen cannot bear witness to what he did because of an absence of experience so complete that his testimony becomes mere chatter, revealing nothing of the truth, only illuminating the impossibility of comprehension and moral self-knowledge.

While Teunissen’s figure doesn’t occupy an ambiguous moral territory, the framework of examining collaboration and moral compromise without simplistic judgement provides a sophisticated, multi-perspective representation of the perpetrator. Although any kind of reconciliation with what happened may be unobtainable, but the documentary also isn’t only a remorseless return to the crimes and the wish for their public acknowledgement. Bouwman’s film contributes to perpetrator documentary scholarship because it challenges simplistic narratives and reveals how the system of domination depends equally on true believers and ambitious careerists willing to suppress moral reservations.

This dynamic of complicity through opportunism disturbingly resonates in contemporary digital contexts, where movements also recruit through opportunity and access rather than ideology alone. While classical propaganda was directly top-down and centralized broadcast, nowadays it’s also decentralized, and the mechanism became more sophisticated and effective. Sharing and promoting propagandic content, fake news and misinformation in digital platforms not only influencing, but potentially harmful, making the nature of responsibility and complicity more complicated.

Sources:

Koch, J. J. I. (2023). The Ethics of Representing Perpetrators in Documentaries on Genocide. European Journal for Cultural Studies, Volume 27, Issue 5, 928-946.

Rapold, Nicholas (2024). Crimes of Opportunity: Luuk Bouwman on His Portrait of a Nazi Official, ’The Propagandist’. https://www.documentary.org/online-feature/crimes-opportunity-luuk-bouwman-his-portrait-nazi-official-propagandist

Agamben, Giorgio (1999). Remnants of Auschwitz. The Witness and the Archive. New York, Zone Books. 33-39.

The article was created as part of the UniVerzió program, in collaboration between the Verzió Film Festival and the Department of Film Studies at Eötvös Loránd University. Instructor: Beja Margitházi.